Luke Serafin

Gameplay/Systems Designer

Here are some of the games I've designed

Take a look around

warball

Pure Destructive Chaos!Action-packed destruct-a-thon

with intense and satisfying combat

gameplay / weapons / ai

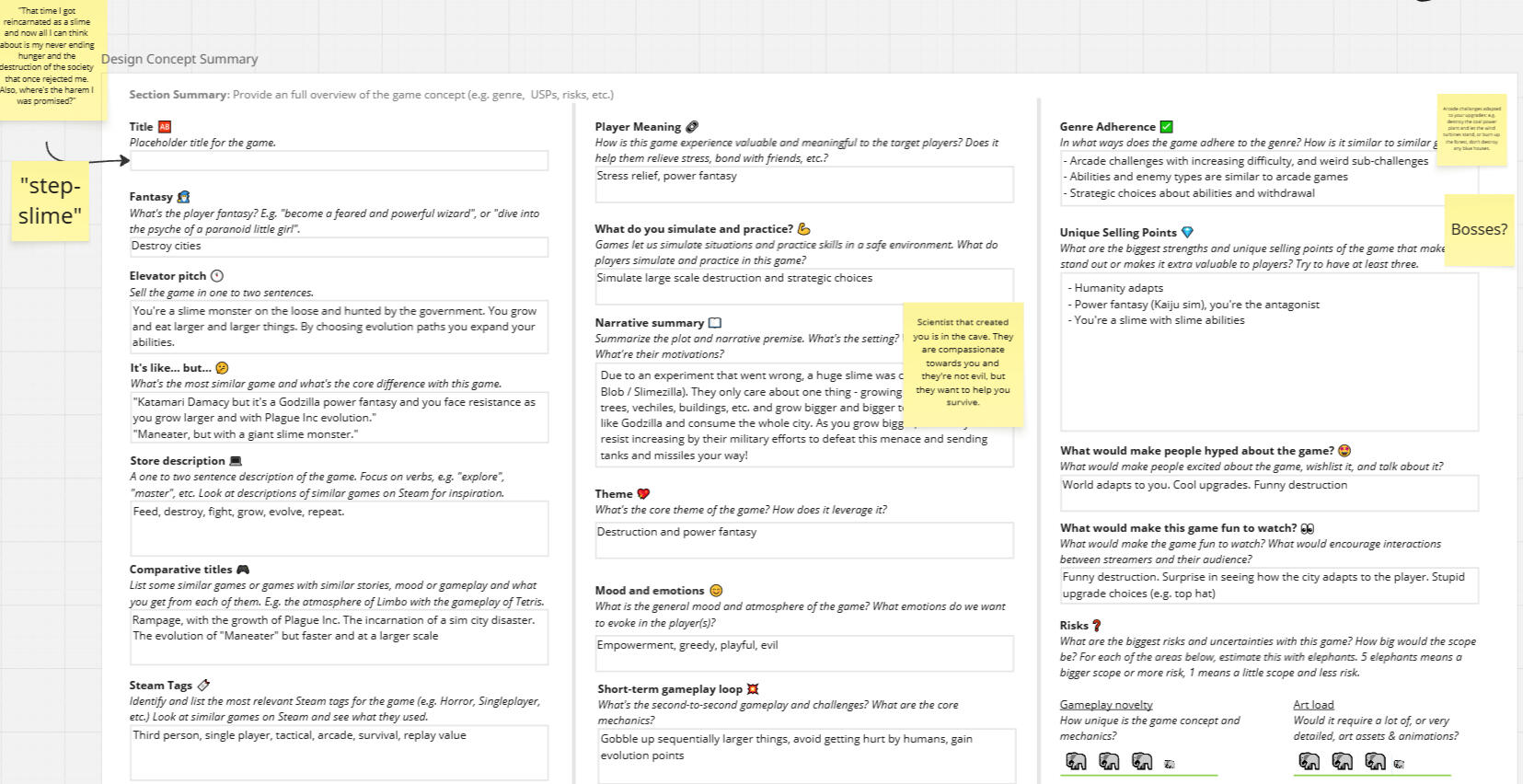

Goozilla

Eat. Grow. Destroy!Pick-up-and-play roguelike

power fantasy.

Abilities / Upgrades / Progression

Overdosed

Stressful Quick Thinking!Casual panic inducing fast paced puzzle-ish game

Gameplay / Onboarding

Prototypes

A collection of small prototypes and experiments that are worth mentioning but aren't big enough to warrant their own section.

Gameplay / Systems

Overview

Goozilla is a game I developed as a Futuregames game project in a team of 4 designers and 4 programmers, everyone working full time with standard working hours. The lack of artists meant that designers were also in charge of finding and implementing premade assets. As is standard practice for game projects at Futuregames, the environment mimics that of a real workplace in the industry. Our team had roles such as project owner, scrum master, and team leads, with the school acting as shareholders / upper management setting deadlines for alpha, beta, feature freeze, etc. We received a total budget of 1000 SEK for purchasing assets from Fab. The budget could also be used for version control solutions to avoid some very badly timed perforce issues.

In this project a large emphasis was put into the ideation and pre-production process. Roughly a third of the entire time spent on the project was spent brainstorming and iterating on different ideas and prototypes. At the start even the genre of what we were making was completely up in the air, which is why this entry will be focusing mostly on the process of collaborating as a team to bring forth a solid and fleshed out concept from start to end.

In the end, the game that we ended up with is a vampire survivors inspired pick-up-and-play roguelike with chaos and destruction front and center. You play as an all-consuming and ever-expanding blob of slime with crazy elemental abilities that evolve as you feed on buildings, vehicles, and whatever else you might find in the city to grow larger and more powerful. Become a city-munching kaiju and fight off the military as humanity desperately tries to stop you!

Brainstorming

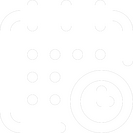

The first thing we all did was gather around a table with a whiteboard and sticky notes and started throwing around ideas. When we were assigned this project we were given the theme of "Antagonist". So That's where we started. Anything we could think of that could relate to the concept of an antagonist, we wrote on a sticky note and placed on the board. Afterwards we sorted all the notes into different categories.

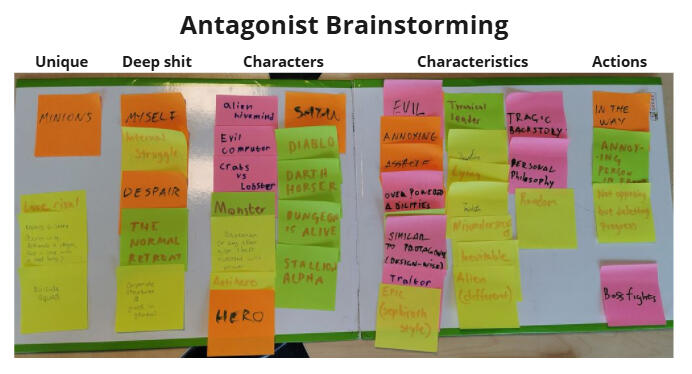

The same also goes for AI

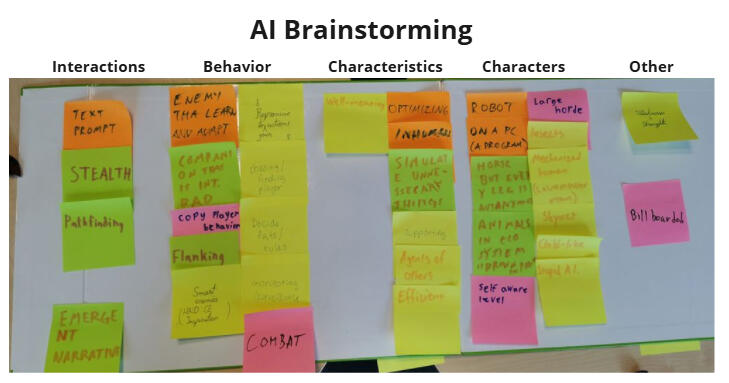

Lastly we all wrote on the board what genres we were most interested in making. We then each got three votes to decide on what was the overall favorite genres among the team, which we then centered the rest of our ideas around.

Ideation

Our next task was to come up with as many game ideas as we can, pulling from the concepts and genres we brainstormed earlier. In total we came up with 31 total game ideas with varying levels of complexity. By using the same voting system as before we narrowed it down to 8 by eliminating ideas that got less votes until we had one idea per person. Each person then elaborated on the ideas in 4 different categories:

Genre

What's the genre? Be as specific as possible, e.g. "Psychological Horror Visual Novel". Use the Steam tags for inspiration.

It's like... But...

What's the most similar game and what's the core difference with this game.

Gameplay

What do you do in the game? What actions drives the gameplay loop? What's the main objective and challenge? How do you win/lose?

Target Audience

Describe the target audience and be as elaborate as possible. Are they causal or serious gamers? What genres do they play? Why and when do they play games?

Now that we were really sure about what each game idea had to offer we did yet another round of eliminations and narrowed it down to just three ideas to further expand on and prototype.

The Three Prototypes

We split the team into three and got down to business in Miro and expanded on the concepts even further using the same methodology as before. (A lot of Miro-ing was done that day)

This brilliant worksheet was formulated by our great team lead and scrum master Jakob Ferenius

Once we were done ideating for good we sent off the programmers to do their own thing and us designers spent the next three days prototyping our games in parallel.

The Great Decision

Once the three prototypes were ready it was time to present them to the great jury of industry veterans to get the greenlight (scary). In reality it wasn't that scary. We just had a casual chat about the pros and cons of each game. Later we all sat down one last time to once and for all determine which game we should continue with. We decided on three different criteria to discuss for each game: What we are excited about, what aspects are relevant to our specializations, and any concerns we have with the game. Finally based on that discussion we did one final round of voting to select the winner. And then one more round of voting because it ended in a tie.

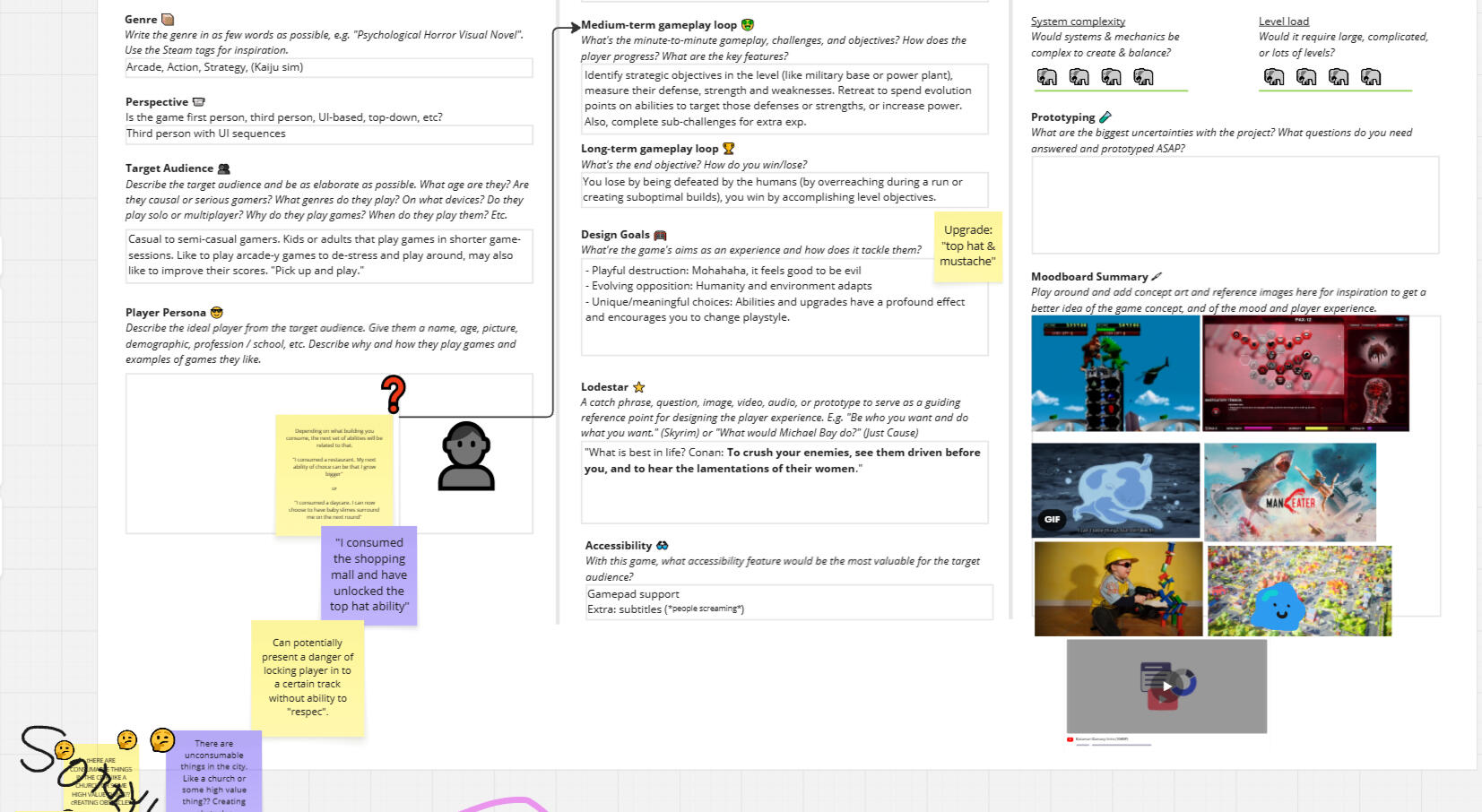

Locking In The Details

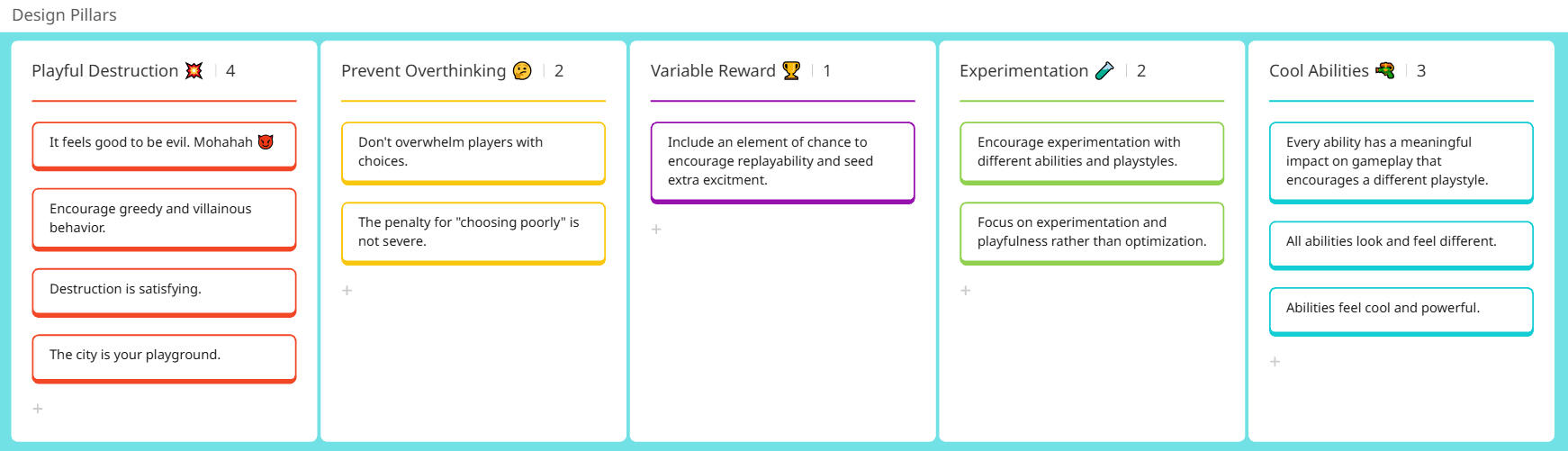

Now it was time to get everyone on the same page and establish some core design principles and pillars. We went for a really simple player centric approach that focused on incremental changes and constant playtesting to minimize assumptions and overthinking. Every time we added anything significant we would bring on a random person and have them playtest it.

Our design pillars all work to serve the simple goal of making the player feel good. The game is meant to be a power fantasy where you feel powerful and almighty, and we didn't want the player to struggle for that feeling, so we wanted to avoid punishing the player too much. That sort of accessibility was important to us and we wanted the pillars reflect that as much as possible.

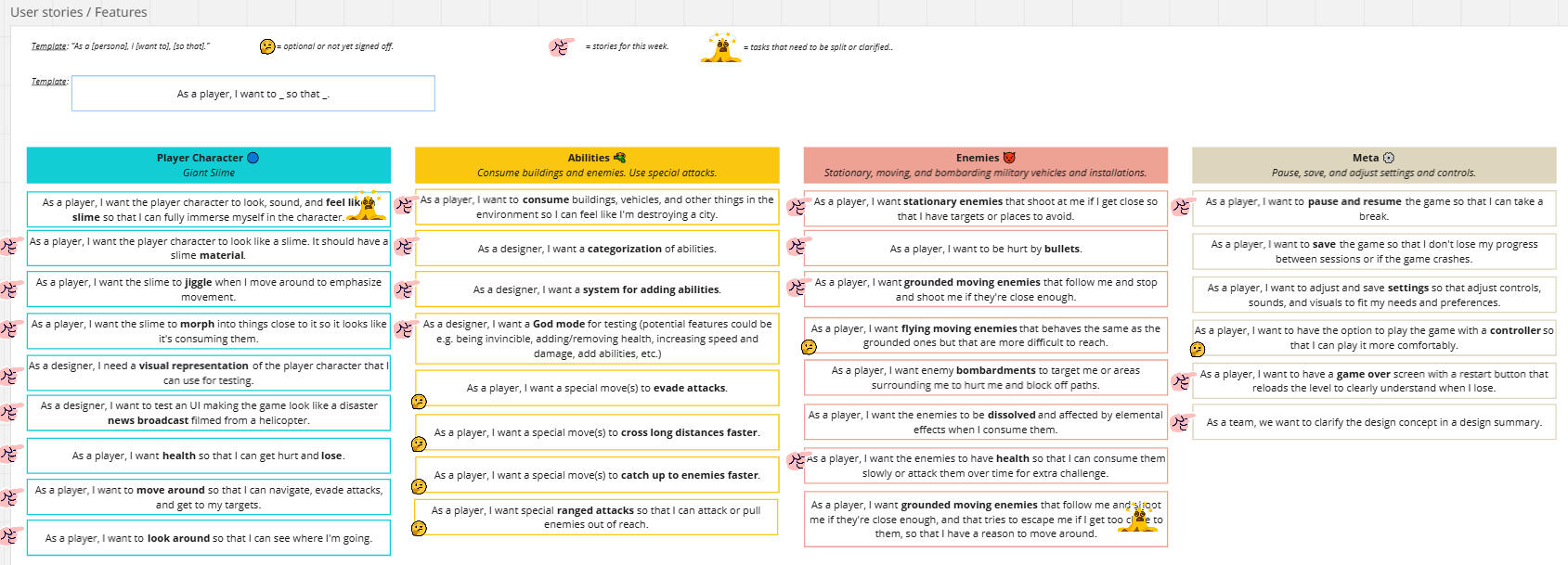

To streamline our development process and especially communication, we made heavy use of user stories to describe the features that we wanted in our game. The goal was to prevent misunderstandings by always involving a human perspective to clarify the intent of the feature. This was overall very effective at keeping our vision of the game aligned with each other.

What I Brought To The Table

While all of the above is a cool story and all, I don't actually have that much presence in it. This is quite simply because I didn't make the winning prototype. Does this mean all that time was wasted? Not at all, with these sorts of things it's either take it or leave it, and I chose to take it elsewhere and put it on a little figurative shelf for later because a good prototype is a good prototype. This is not to say I didn't contribute anything to the final product, far from it. I designed the main progression system and all the abilities within it (kind of a big deal in a genre about collecting abilities and becoming stronger). And so the rest of this entry will cover the sweet and juicy details of how I made that happen.

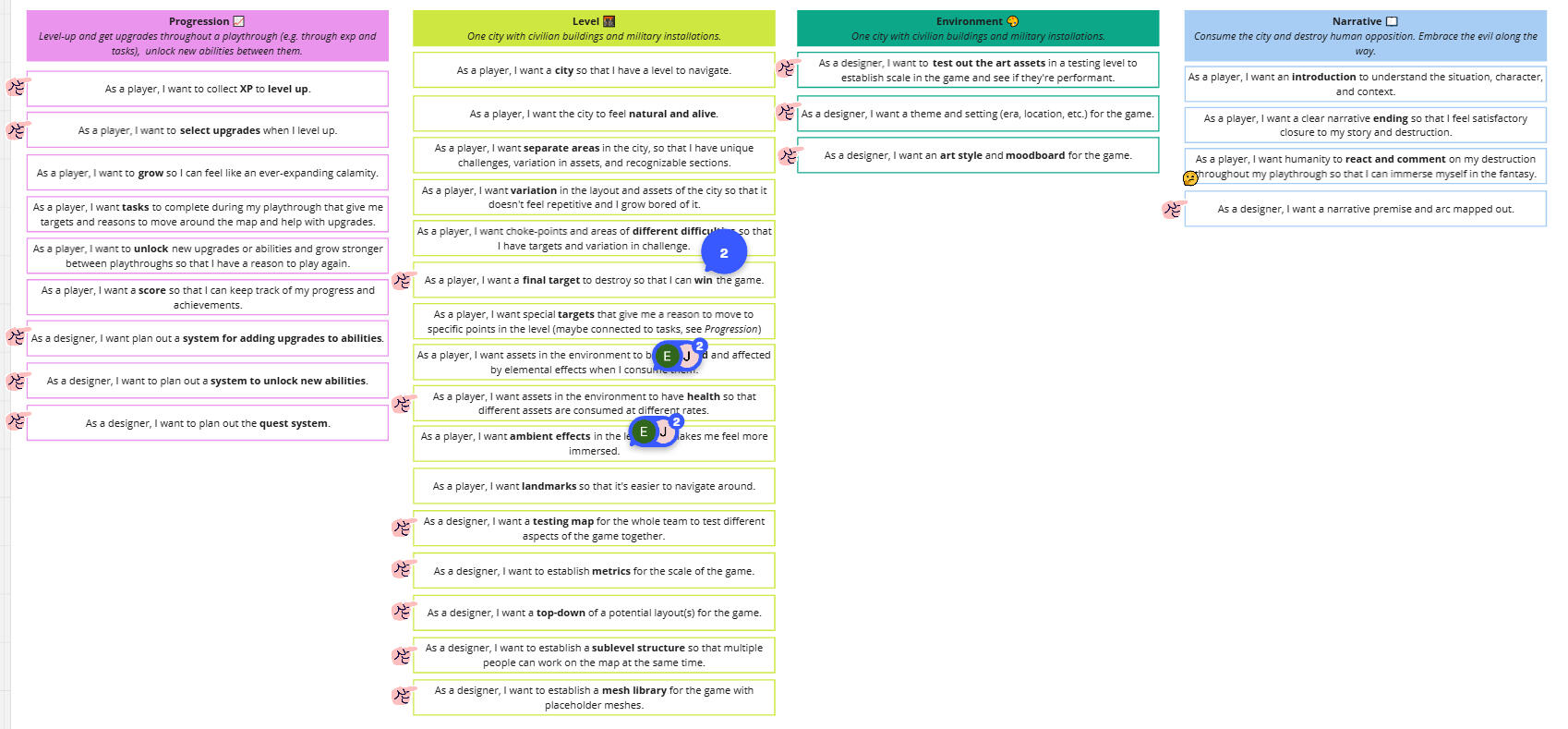

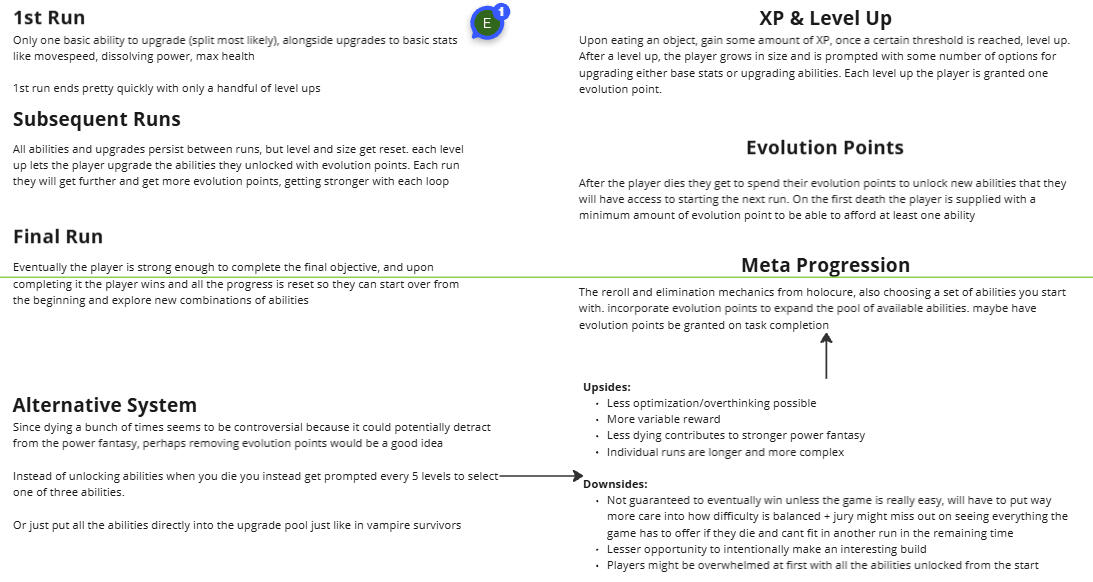

Progression

Arguably the most important element of a roguelike, my first task was putting together a system of progression that fit with our vision of the game. Initially I went with a "roguelite" one step back, two steps forward approach. The player would spawn in, eat some stuff, get stronger, die, and then receive a super powerful unique ability to carry over into their next life so they can get further than last time. After enough attempts the player would eventually get strong enough to reach the end and win the game, regardless of their initial skill level.The goal was to make the most out of a limited set of unique abilities and introduce them slowly to extend playtime and let the player get accustomed to their current abilities before introducing more, while still keeping the moment to moment gameplay exciting and dynamic by giving the player simpler upgrades and progression that reset after each life. This would also allow for some level of experimentation within each full run of the game.This system succeeded in contributing to many of our design pillars by making failure a core part of progression. Even if the player fails they are still progressing. As there is no true fail state, players are encouraged to get playful and greedy, constantly taking big risks since there is nothing to really lose. This system also accounts all skill levels by gradually raising the difficulty until it is too much for the individual player, the difference between skill levels being how far they get each life. This also rewards the more skilled players by giving them a bigger reward at the end of each life, encouraging replayability beyond just experimenting with new strategies.

Unfortunately this system was a bit controversial. The general opinion was that dying repeatedly contributed negatively to the power fantasy (very valid). There were also some concerns about the playtime getting drawn out too far, our intent was for a full run to take roughly 20 minutes and that the game shouldn't take too long to get exciting. So changes were in order.We decided to do away with the whole dying repeatedly thing and instead we integrated the abilities into the regular pool of upgrades and balanced the game around that. This made the game a lot more fast paced overall, pivoting toward a more pick up and play arcade style game.

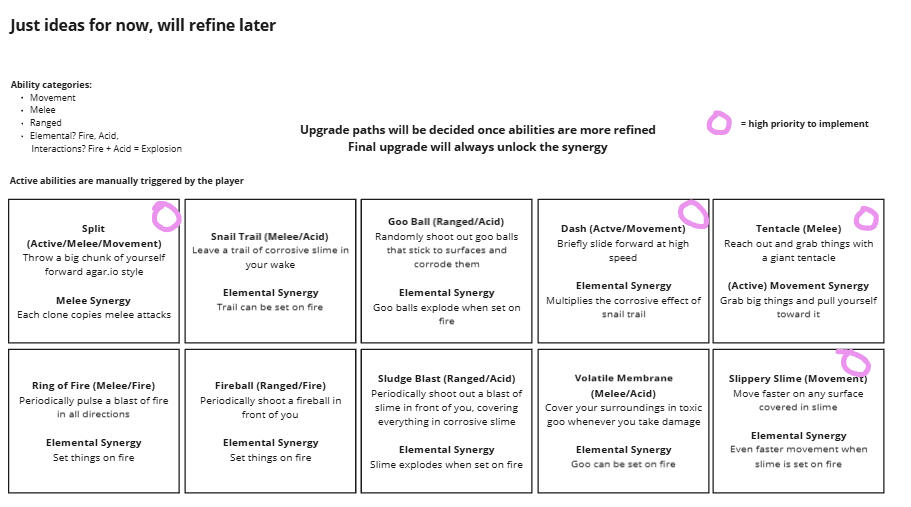

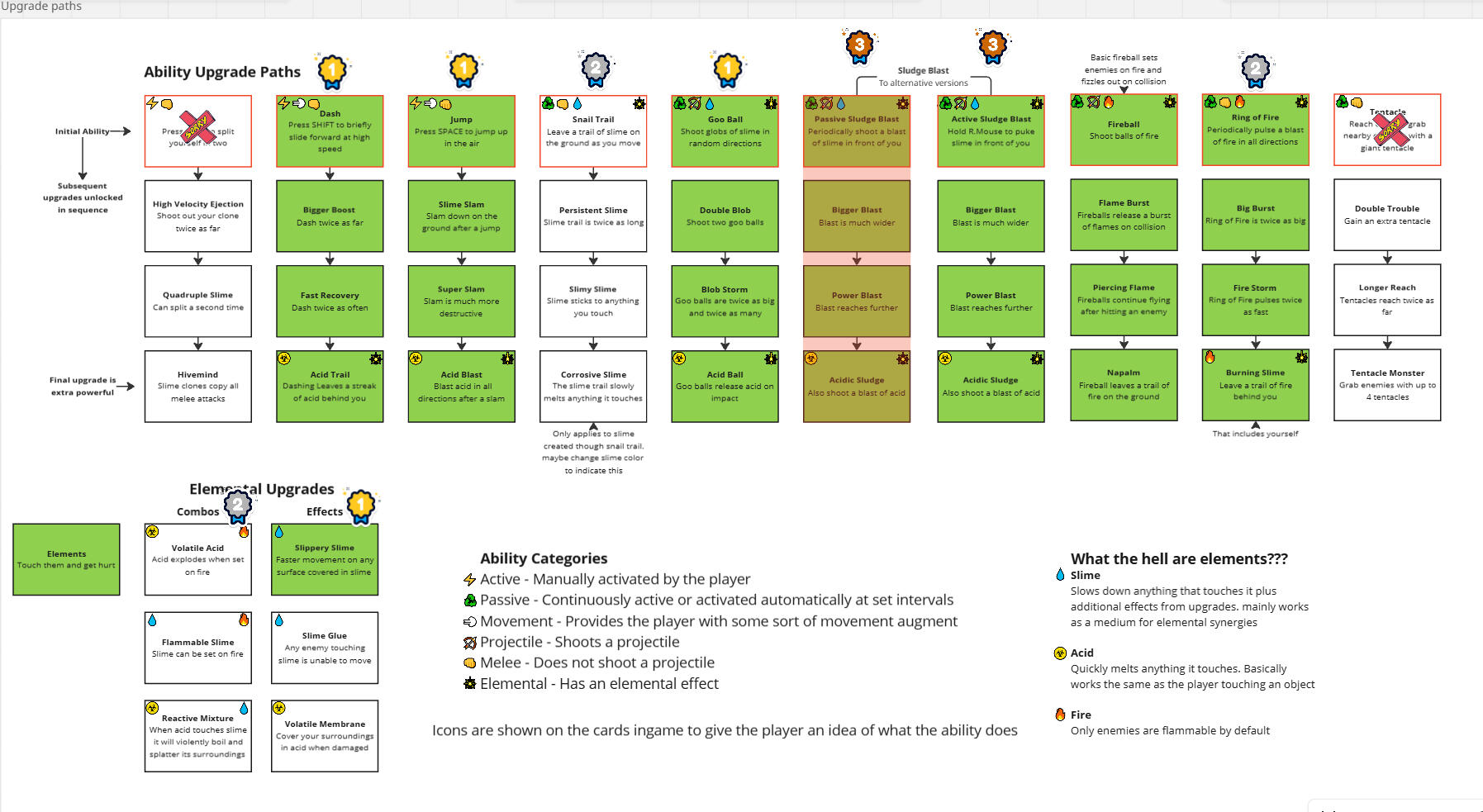

Abilities

When designing the abilities I took great care to make an even spread of very distinct abilities that all had a unique situation where they were super effective. Ideally I wanted the abilities to be powerful, but not all encompassing, otherwise new abilities wouldn't feel as powerful when you already have one, each upgrade needed to be impactful and let you do something you couldn't do before. I wanted a system where the player could pick abilities based on what most suited their playstyle, either to empower their strengths or cover their weaknesses.When there are many abilities at once I find it important to avoid overlapping function and instead focus on ways that certain abilities can empower each other. So I devised a system of elemental attributes that let abilities interact with each other. For example, you could have an ability that covers something in corrosive slime, slowly destroying it, and an ability that sets something on fire, also slowly destroying it. Combined together in the same place it would cause a big explosion, quickly destroying many things. Sadly this system was cut to avoid scope creepTo keep abilities distinct I made a set of categories for the abilities to fit into, and made sure that none of the categories had either too few or too many abilities that corresponded to them. Note how the abilities are an even mix of long range / short range / movement, and that each element has two abilities that correspond to them. Even when some abilities were eventually cut we were very thoughtful about preserving this balanced spread of differing functions.

We wanted the abilities to improve and grow over time with upgrades, both as a way to make the player grow stronger over time, but also as a way to make the abilities less overwhelming for new players. I gave each ability 3 additional upgrades that each add something new to its capabilities, with the last upgrade being extra impactful.To actually add all these abilities to the game and help with balancing I collaborated with another designer, they helped with implementing some of the abilities and mainly building the technical infrastructure to make things work. Together we prioritized which abilities were needed the most in the game. From the start I tried to keep the system as modular as possible and made sure that it would still hold up even when parts of it are eventually cut and modified due to inevitable pivots and time constraints that are almost universal in this profession. I'm proud to have made such a robust system, as that planning and thoughtfulness really paid off in the end with the whole system still working well even when most of my initial plans never made it into the final product.

Engine

GameMaker Studio 2

Team Size

2 Full Time + 3 Part time

Dev Time

32 Days + Occasional Overtime

Overview

WARBALL is a game I developed together with some classmates in our final year of highschool. The game was developed using Game Maker Studio 2 over the span of about 8 months with the team coming together once a week to work on it. The team consisted of 5 people originally, but in the end it became a mostly two man job with the main sprite artist and I making the vast majority of the content visible in the final product.

My initial vision for the game was an action-packed shmup-type game where the main objective is to cause as much destruction as possible while fighting off a barrage of enemies. I borrowed a lot of aspects of the gameplay and design philosophy from games like Nuclear Throne and Doom Eternal, then used my own intuition and design thinking to merge the ideas into a cohesive and well rounded experience.

Design Pillars

To meld together all these ideas I needed a good foundation to rely on. To create this foundation I decided on three main design pillars that every mechanic should seek to fulfill in some way. These pillars all work together with the goal of making the combat as fun and exciting as possible and greatly reward skilled play.

● Adaptation

The player should be challenged to quickly adapt their strategy to any given situation and prioritize different aspects of their gameplay in the heat of battle.

● Excitement

The player should be constantly pushed to play at their limit and the most effective playstyles should also be the most fun and exciting.

● Expression

The player should always be incentivized to engage with all the tools at their disposal and express themselves through unique combos and interactions.

Note: The following is a deep dive into my thought process and intentions when designing this game. It is very long and wordy so bear with me.

Weapons

The player’s arsenal is designed to function like a toolbox with each weapon serving its own purpose. Every weapon is designed to have a distinct weakness but be very powerful when everything lines up just right. The arsenal fits together in such a way that each weapon's strength covers another's weakness. This creates a gameplay loop where the player is constantly encouraged to switch weapons to counter whatever situation the game throws at them.

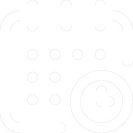

Gun

A 2-in-1 type gun that can deal small but easy chip damage at range but can be a devastating tool of destruction up close.

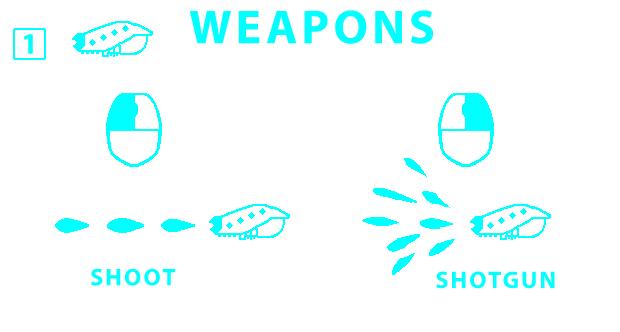

Rifle

A slow but powerful laser rifle that pierces straight through everything in its way. Can be charged up for more power.

Launcher

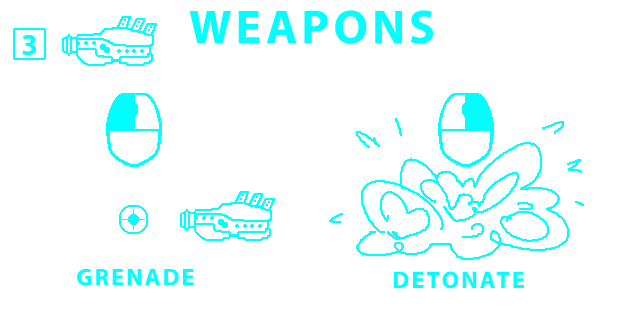

Launches explosive grenades that detonate on command. They are very destructive but can only be used sparingly.

As shown in the graphics, each weapon has a more powerful secondary attack on top of their regular attack. This works as a way to sneakily add more weapons and mechanics without making the game too complicated. Each secondary attack also has a distinct weakness. The shotgun is only effective up close where you can’t react fast enough to avoid incoming damage on top of having a much slower fire rate. This makes the shotgun a quick get-in get-out type weapon as opposed to the more spammy primary attack. The charged laser also has the downside of being slow to charge up and having a very long cooldown period, leaving the player defenseless for a moment.

Enemies

What good are all these cool weapons with nothing to shoot at? Well here they are. The design of each enemy is very simplistic and purposeful to easily understand their role and threat level in a fight. The presence of each enemy calls for a specific response, providing dynamic gameplay and forcing quick thinking and decision making mid firefight.

Grunt

Basic cannon fodder enemy. Provides skilled players with free projectiles to parry but can easily overwhelm you if left unchecked. they will attempt to seek out cover and harass you from safety, incentivizing the destruction of said cover.

Chaser

Highly deadly kamikaze bomber. Upon making line of sight, the chaser emits a distinct noise to alert the player of incoming danger. Demands the player’s full attention and requires proper use of defensive abilities to avoid. Forces the player to make a split second decision to either dash out of the way or parry it into some enemies. Failure to react fast enough will quickly result in a very painful explosion to the face followed by death.

Decimator

Slow but fearsome tank with deadly and destructive attacks. Requires the use of high damage combos to take out effectively. Charges up a big laser that cannot be blocked and deals enough damage to kill the player many times over if taken head on. It has a clear telegraph when charging that tracks the player leaving only a small window to dodge. It also shoots two missiles from either side that converge on the player’s position and explode on impact. They can be easily reacted to from a distance but up close they can punish the player for being too reckless. These two attacks provide for very dynamic combat as the laser gets easier to avoid at close range due to the decimator’s slow speed, but get too greedy and you might get surprised by the missiles.When fighting a decimator the player is forced to make larger scale decisions on which threats to take out first. Take out smaller threats while enduring the constant pressure to later fight the decimator in a more controlled environment, or run in guns blazing and immediately go for the big kill amidst the chaos.

A Common Pitfall

One thing that often happens in games that have a varied arsenal of weapons is that the players always seem to gravitate to one single weapon that happens to suit their initial playstyle the best. This then leads to a feedback loop of the player getting better at using that weapon, and then refining their playstyle to be even more centered around it. So when they try using a different weapon they get punished for it because they have no practice with the weapon and no way of fitting it into their playstyle. The problem with this is that these games are usually designed around using all the weapons in tandem, so doing that is always going to be the most fun. Not to mention that by only using one weapon the player ends up missing out on a large amount of the mechanics that the designers spent so much time making.

And How I Avoided It

The way I went about preventing players from falling into this boring comfort zone is by making sure each weapon has very defined strengths and weaknesses. Additionally, the enemies and the layout of the levels are designed to exploit those weaknesses. But where one weapon falls short, another shines brightly. This rock-paper-scissors dynamic makes sure that when the player tries to hammer in a nail with their screwdriver because it’s their favorite tool, it ends up not working very well as they will very quickly end up in a situation where that strategy falls flat. But when they properly utilize their entire toolbox and make good decisions on what to use they get rewarded by becoming an unstoppable force of destruction.

More Mechanics

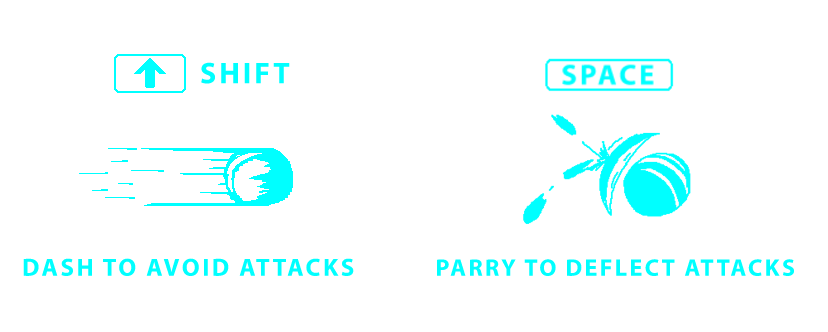

Satisfying combat needs more depth than just “shoot enemy to win”. It requires decision making, risk assessment, and skill expression. I covered decision making in the previous section, but what about risk assessment? I consider managing risk and pushing the limits of what you can and cannot get away with to be one of the cornerstones of satisfying gameplay. The simplest way to accomplish this is with the concept of risk vs reward. Give the player 2 options, one of the options is difficult and risky, and the other is easy and consistent. If the result is the same then players are always going to use the easiest option, even if it’s not as fun. But if you properly reward the player for challenging themselves then it becomes a decision worth making. Combine that reward with some nice feedback and you’ve turned a useless mechanic into your very own dopamine generator. So how does mine look? When the player is about to take damage they get two options: Shift or Space.

| By dashing, the player gains a quick burst of speed and a brief period of invincibility to easily avoid incoming damage and reposition. | By parrying, the player gains a temporary forcefield that deflects incoming fire and supercharges it to explode on impact. |

The player is forced to decide whether to dash and avoid the danger or to hit the timing window for the parry to return the danger right back to where it came from. Both abilities can be used at any time and both fill similar roles in the player’s arsenal. But the parry is much harder to perform. The forcefield only lasts for about 0.2 seconds so the player needs precise timing to not get hit by whatever they are trying to deflect. In exchange for that risk the player is rewarded with one of the most powerful attacks in the game.

Skill Expression

Skill expression is an important part of making a player feel engaged with the mechanics and create a tangible feeling of progression as they get better at the game. A lot of games create this progression through upgrades that get unlocked throughout the game. But implementing that is a lot of work and is hard to balance so I went with a different approach. Instead of locking mechanics behind progression barriers I lock them behind skill barriers. If a certain trick is too difficult to execute for a new player, then in essence, that trick gets “unlocked” once they get better at the game. Once the player gets good enough they get to express themselves through the use of these advanced tricks and become more powerful as a result.

These extra tricks and interactions let the player add a rocket launcher, Gatling gun, and flamethrower to their arsenal of rock, paper, and scissors, but only if they are up to the task of mastering these more difficult mechanics. This allows for many new ways of approaching a given situation depending on the current skill level of the player. A high level of skill expression also adds plenty of replay value to the game as players can revisit earlier levels with fresh new tricks up their sleeves for even more destruction than last time.

One notable example of these advanced mechanics that I’m extra proud of is what I like to call the grenade snipe. If the player shoots out a grenade, instead of detonating it they can choose to shoot it with a laser to supercharge it and create a much bigger explosion. While being a little tricky to set up and requiring some precise aim this combo can be incredibly strong when lined up just right. There is even a stronger version of this combo using the charged laser to shoot the grenade. But with it requiring a lot of time to set up and some pretty precise timing, this version of the combo carries with it much more risk and is very hard to pull off in the middle of a firefight. But if you somehow do manage to pull it off, then expect to clear the encounter instantly because you just nuked the entire room. And probably yourself included, oops.

Overview

Overdosed is a game where you race against time to create cures for dying patients by mixing various ingredients together. It was made as a 3 week long Futuregames game project developed by a team of 4 designers, 4 programmers, 3 artists, and 2 animators/VFX artists. Yes that is 13 people working on a 3 week project and no it did not go well at all. This entry is one about failure, a long series of misguided decisions and bad circumstances that eventually led to half baked game that failed to catch the attention of our target audience. Get ready for an essay because I'm about to explain just about everything that went wrong here how how we could have avoided it.

The assignment was to make a game for children, aged 9-12, themed around science. The game was to be designed around the use of the Xbox adaptive controller, a controller designed to make it possible for people with various types of disabilities to play videogames that they otherwise couldn't. It does this by supporting the addition of various modular attachments that can be specially made to accommodate a wide range of different disabilities.

The Biggest Roadblocks

User-unfriendly human interface

Figuring out what to make was the most difficult task of them all, there were simply too many limitations. While I'm sure the Xbox adaptive controller is great when you use the way it was intended, that wasn't possible for us. Without any attachments the controller is just a brick with two massive buttons and a barely usable dpad. Unpleasant to use even as a fully able person. Designing a game with only two buttons is very challenging and eliminates many potential ideas.

Afraid to make anything challenging

Our first thought when we saw the big massive bongo buttons was to make a rhythm game, but this idea was quickly discarded because we wanted to make something easy and accessible. Since we were designing for children we wanted the game to be simple to play and not require any advanced inputs like simultaneous button presses or strict timing. Additionally we wanted to be mindful of disabilities so we wanted to avoid relying on audio cues or color recognition.

Taking the path of most resistance

We considered making an endless runner but thought that would be lame and unoriginal because that's the easy answer. GP1 projects were infamous for being nothing but endless runners and we wanted to try being unique. After countless hours of pointless prototyping and struggling to find ideas that fit the theme and restrictions we eventually gave up, and despite our best judgement we turned to the plus-shaped elephant in the room.

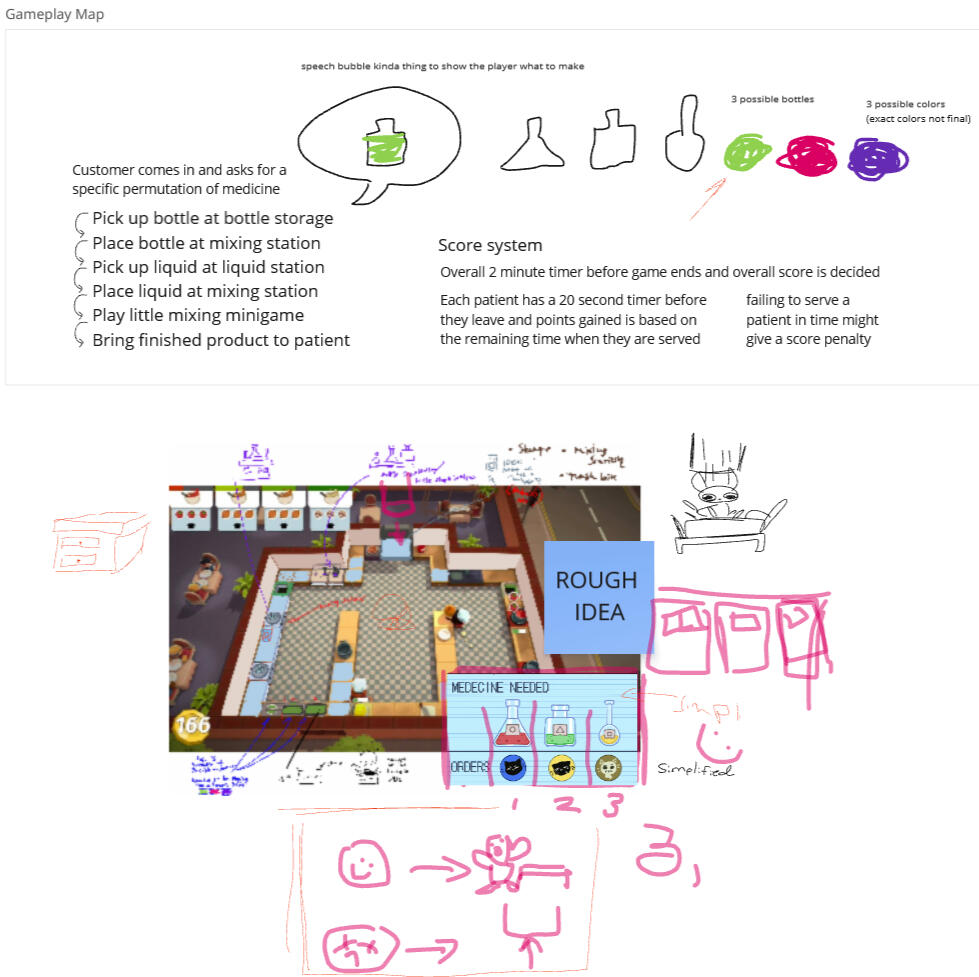

Limiting ourselves into unsuitable gameplay

We begrudgingly decided to use the heavy duty industrial finger breaking dpad despite our very valid concerns that children might lack the physical might to register any inputs on it. We figured that as long as we didn't make them hold down the directional buttons it should be fine (it was not). The use of the dpad did open up a lot of options because we now had directional movement input. With our small amount of creativity already spent we decided to simply take an already existing game and re-theme it to be science oriented. We borrowed the idea and gameplay from Overcooked, replaced the food with medicine, and simplified the game as much as we could.

Overcomplicated Production

We didn't just borrow our idea from Overcooked, we even overcooked our production pipeline! When doing the gamedev equivalent of forcing a fully staffed kitchen to collaborate on the same sandwich, things are bound to get messy, especially when its everyone's first day on the job. The vast majority of us had no idea how to even use version control, let alone how to work with issue tracking tools and agile workflows. And yet we still decided to create a complex workflow that involved multiple git branches, a 7 column trello board, and a convoluted folder structure with strict rules on what to push. By the end of the week we had barely even started working on the project because everyone was so confused about how to actually submit any work. Despite all this the closest thing we had to a game design document was just this random Miro scribble:

Needless to say our daily standups were frequently over an hour long just clear up all the misconceptions about what the game even is.

Hopeless Onboarding

The onboarding/tutorial of this game is by far the biggest disaster so far, and I'm allowed to say that with no shred of respect or remorse because I was solely in charge of it. Sure it looks clean and simple, and manages to effectively direct the player through the first level without any words, as one of our design goals was to make the game fully playable without needing to read.There is just one slight problem with it. It does not teach the player a single thing. All the tutorial does is point arrows at whatever object you need to interact with. It does not teach the player what those objects do. It does not teach the player why they need to go to those objects. It does not teach the player what they are trying to accomplish or what the goal of the game is or how to even find out what your current task is. It completely falls short at teaching anyone how to play the game to the degree that not even adults understand how, let alone 9 year olds.

The real crux of the issue is that the game is just too complicated to effectively communicate how to play using simple prompts. When first starting the game the problem isn't knowing where to go, it's knowing what your mission is. The player needs to know that there is a dying patient in front of them and they need to be delivered a specific medicine to be cured. This is the very premise of the game and it's not explained anywhere. The player then needs to know to look at the corner of their screen to find the recipe for the medicine they need to make. Also not explained. The player is just expected somehow understand all this at a glance.Maybe if these two things were more effectively communicated my tutorial could have worked. At least then the player would understand what they are doing while they are being taught how to do it. As for how I would communicate these things without words, I'm honestly not sure. At the very least the recipe should have been more in your face, like a speech bubble coming from the patient. The game should also have been simplified, at least in the beginning. As the gameplay designer I had the agency to make it happen but I never even realized the issue until I stood there on the final day having already shipped the game, watching both adults and children alike stand there completely clueless the moment the tutorial ends asking why the arrows are gone.

At the end of week 2 we even had an organized playtest with the very children we were making a game for, but at this point we had not made the onboarding yet so in place of that we explained to the kids what the game was about and how to play. During this playtest they seemed to understand the game just fine, which gave us a false sense of security thinking that the game was actually simple enough for the children to understand. It's obvious in hindsight that the reason they understood the game so quickly back then is because the premise and mission was explained to them. But somehow at the time I did not realize this crucial and obvious detail.

Key Takeaways

Looking back at this project In retrospect I see so much that could have been done differently. With such a short project we would have benefited greatly by just not overthinking it. It was all our first major project in a full team so we got really excited to make something cool, failing to realize that the limitations were put in place to keep the project simple. And as much as I want to blame Futuregames for putting us in such an oversized team with no prior training on how to actually manage a team of that size, sometimes you just have to play the hand you're dealt and find a way though it. Regardless of how we dealt with it, we would have surely run into problems but I think the least we could have done is get things moving quickly and just go with something.

Communication Is Important

Communication was a key factor in this project. Not only the communication within the team but also communicating with children. It's difficult. Keeping the whole team on track when everyone has such unique personalities and ideas is a very complicated task. Everyone has their own impression of what the game is and what it should be, and keeping the teams vision and goals aligned with each other is very important for production to go smoothly. My entry on Goozilla is a great example of how I think this should be done. In that project we had a great design document with a detailed design philosophy to adhere to, strong pillars, and countless user stories and goals that we all worked together to create.Stepping outside the bounds of the team, communicating with children though videogames is a huge challenge. You can't make assumptions about their literacy when it comes to any topic, be that language, or our general understanding of common sense. The way children respond to things is inherently unpredictable, because they don't have the same intuitive understanding of how things typically work that us adults build up through years of life experience. Crafting interactive elements that are universally understood by everyone is a huge challenge, especially when you can't as easily rely on the many established patterns that we are all used to. One of my biggest mistakes when working on this project was underestimating this very challenge.

Simple Game For A Simple Audience

Probably the simplest way minimize difficulty of communicating with children is to keep the tasks as simple as possible. The problem with Overdosed as a kids game is that the gameplay consists of doing one complex multi step process after another. While it's great if we can get children to engage in intellectually stimulating tasks, that was not our goal nor did we have the skill or time to craft an experience that would require that level of testing and insight. Our best bet would be to keep each task simple and self contained and give the children the freedom and agency to explore and interact with the game in a way that makes sense to them, rather than try to explain to them how we think they should interact with the game.

Testing Is Key

One of the biggest things we overlooked was just how important testing is. While it would be very tricky for us to continually find children to playtest things, we should at least have focused more of our efforts on getting our peers to playtest new features. Regardless of who it's from, getting fresh insight on the game is really important and should be done as often as possible. We often fall into the trap of assuming that players will interact with things in the way we intend. But that's rarely the case. During the development process we end up becoming so familiar with our games and how they work that we often forget to convey things to the players that are common sense to us. And we often get blindsided by novel and unintended ways to interact with our systems when we design something with a specific goal in mind. The best way to catch these oversights is to grab a fresh pair of eyes and sit them down with your system to see how they interact with it.

Keep It Simple Stupid

Overcomplicating things that should have been kept simple is absolutely the biggest theme in this project. Us insisting on doing something interesting and unique despite all the limitations we had, and our lack of creativity in creating an idea that met our goals while adhering to the limits of our hardware, just ended with us wrestling a square game into a circular hole. We chose the wrong game to make based on the requirements just because we wanted to be different. Our production pipeline was way too complicated for a 3 week project, slowing down our early work to the point that we missed our opportunity to test our tutorial sequence on the children it was intended for. Overthinking everything yet somehow solving nothing, just digging ourselves into a deeper hole without adressing the fundamental issues. If only we just kept it simple.This simple mantra of "Keep It Simple Stupid" is now something that I live by and always keep somewhere in the back of my mind to stop myself from overthinking things when designing any system, because the best solution is usually also the simplest.

Prototypes

Here is a collection of small prototypes I have made over the years that each showcase a neat mechanic or concept that I think has potential, but don't yet have a full game built around them

This is an idea I had for a puzzle game where the only meaningful input is moving and looking. The main mechanic is that the game always keeps track of where you are looking and seamlessly changes things behind your back. It plays with the idea that in a virtual environment you can only really be sure of what is happening in front of you. If something is out of sight, anything could be happening there and you would have no idea because it isn't shown on the screen. The goal of the game is to escape a maze that keeps sneakily placing you back at the start the moment you stop paying attention to your surroundings. On the walls are cryptic clues that hint at ways to outsmart the maze and avoid its devious tricks